The Black Death

Most infamous of all was the Black Death, a medieval pandemic that swept through Asia and Europe. It reached Europe in the late 1340s, killing an estimated 25 million people. The Black Death lingered on for centuries, particularly in cities. Outbreaks included the Great Plague of London (1665-66), in which one in five residents died.

The first well-documented pandemic was the Plague of Justinian, which began in 541 A.D. Named after the Byzantine emperor Justinian I, it killed up to 10,000 people a day in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey), according to ancient historians. Modern estimates suggest half of Europe's population was wiped out before the plague disappeared in the 700s.

The cause of plague wasn't discovered until the most recent global outbreak, which started in China in 1855 and didn't officially end until 1959. The first breakthrough came in Hong Kong in 1894 when researchers isolated the rod-shaped bacillus responsible—Yersinia pestis. A few years later, in China, doctors noticed that rats showed very similar plague symptoms to people, and that human victims often had fleabites.

The animal reservoir for plague includes mice, camels, chipmunks, prairie dogs, rabbits, and squirrels, but the most dangerous for humans are rats, especially the urban sort. The disease is usually transmitted by the rat flea, Xenopsylla cheopis.

Yersinia pestis

A microscopic image shows Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that causes plague.

© Photodisc/Thinkstock

Types of Plague

Bubonic plague, the disease's most common form, refers to telltale buboes—painfully swollen lymph nodes—that appear around the groin, armpit, or neck. Septicemic plague, which spreads in the bloodstream, comes either via fleas or from contact with plague-infected body matter. Pneumonic plague, the most infectious type, is an advanced stage of bubonic plague when the disease starts being passed directly, person to person, through airborne droplets coughed from the lungs. If left untreated, bubonic plague kills about 50 percent of those it infects. The other two forms are almost invariably fatal without antibiotics.

Yersinia pestis is extraordinarily virulent, even when compared with closely related bacteria. This is because it's a mutant variety, handicapped both by not being able to survive outside the animals it infects and by an inability to penetrate and hide in its host's body cells. To compensate, Y. pestis needs strength in numbers and the ability to disable its victim's immune system. It does this by injecting toxins into defense cells such as macrophages that are tasked with detecting bacterial infections. Once these cells are knocked out, the bacteria can multiply unhindered.

Victims are so overwhelmed that they're more or less poisoned to death as the bacilli gather in thick clots under the skin, where a passing flea might pick them up. Other grim side effects can include gangrene, erupting pus-filled glands, and lungs that literally dissolve.

The second pandemic of the Black Death in Europe (1347–51)

Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Oriental rat flea

Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis), primary vector for the transmission of the bacterium Yersinia pestis between rats and humans.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

The rate of mortality from the Black Death varied from place to place: whereas some districts, such as the duchy of Milan, Flanders, and Béarn, seem to have escaped comparatively lightly, others, such as Tuscany, Aragon, Catalonia, and Languedoc, were very hard hit. Towns, where the danger of contagion was greater, were more affected than the countryside, and within the towns the monastic communities provided the highest incidence of victims. Even the great and powerful, who were more capable of flight, were struck down: among royalty, Eleanor, queen of Peter IV of Aragon, and King Alfonso XI of Castile succumbed, and Joan, daughter of the English king Edward III, died at Bordeaux on the way to her wedding with Alfonso’s son. Canterbury lost two successive archbishops, John de Stratford and Thomas Bradwardine; Petrarch lost not only Laura, who inspired so many of his poems, but also his patron, Giovanni Cardinal Colonna. The papal court at Avignon was reduced by one-fourth. Whole communities and families were sometimes annihilated.

Consequences

The consequences of this violent catastrophe were many. A cessation of wars and a sudden slump in trade immediately followed but were only of short duration. A more lasting and serious consequence was the drastic reduction of the amount of land under cultivation, due to the deaths of so many labourers. This proved to be the ruin of many landowners. The shortage of labour compelled them to substitute wages or money rents in place of labour services in an effort to keep their tenants. There was also a general rise in wages for artisans and peasants. These changes brought a new fluidity to the hitherto rigid stratification of society.

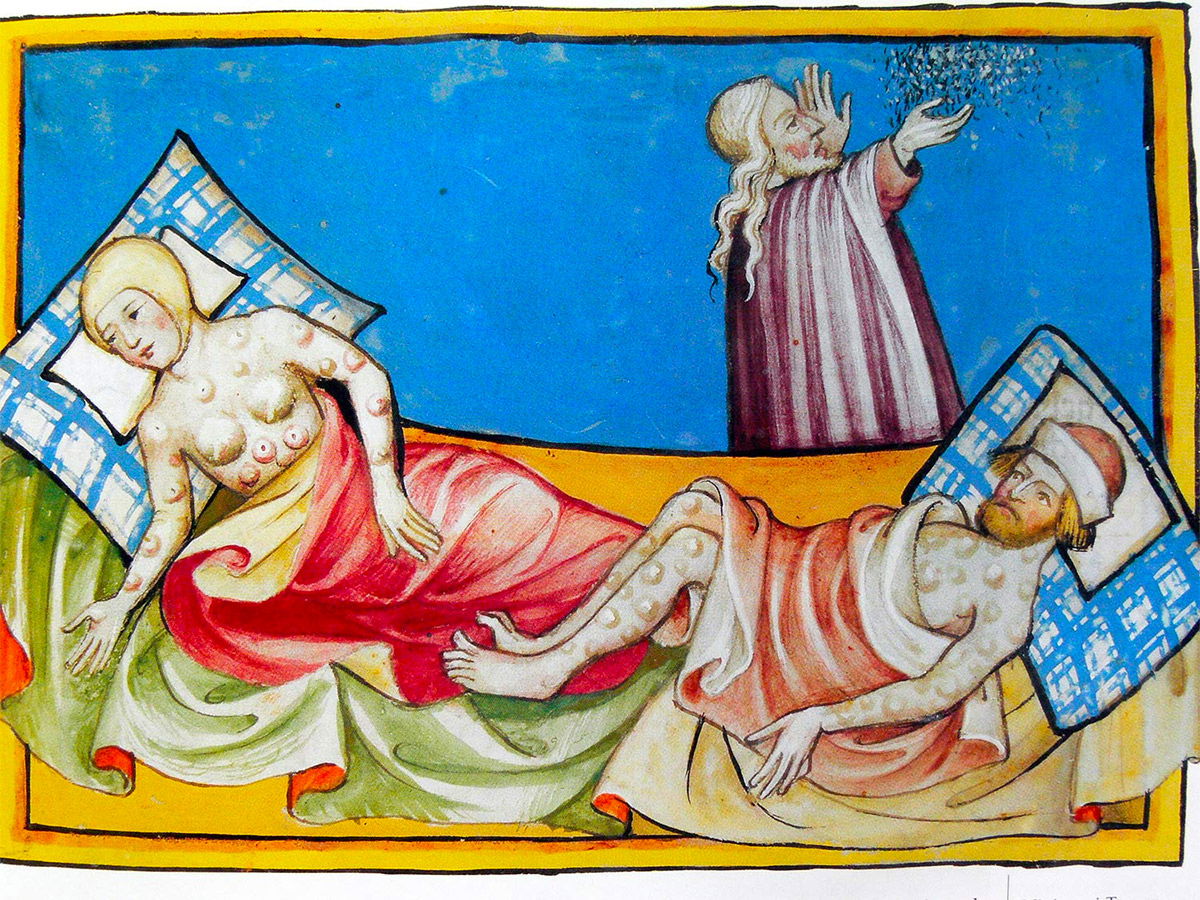

Black Death

Plague victims during the Black Death, 14th century.

Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine

The psychological effects of the Black Death were reflected north of the Alps (not in Italy) by a preoccupation with death and the afterlife evinced in poetry, sculpture, and painting; the Roman Catholic Church lost some of its monopoly over the salvation of souls as people turned to mysticism and sometimes to excesses.

Anti-Semitism greatly intensified throughout Europe as Jews were blamed for the spread of the Black Death. A wave of violent pogroms ensued, and entire Jewish communities were killed by mobs or burned at the stake en masse.

The economy of Siena received a decisive check. The city’s population was so diminished that the project of enlarging the cathedral was abandoned, and the death of many great painters, such as Ambrogio and Pietro Lorenzetti, brought the development of the first Sienese school to a premature end.

Source:

- www.nationalgeographic.com

- www.britannica.com

Source:

- www.nationalgeographic.com

- www.britannica.com

No comments:

Post a Comment